What you can learn from Columbo

"Who would you rather discomfort – the guy in the Gulfstream or the one on a bicycle?" – Andrew Jennings

By Mark Lee Hunter

The best real-life investigator I ever met is a gendarme named Jean-Louis Bertrand, who recently retired with the rank of colonel, decades after he entered the force as an enlisted man. He could make a stone talk, and if the stone told only lies, he would verify every one, and that would tell him what the stone wanted to hide.

He said, “I’m like Columbo – a friend of the ordinary, honest people.” And a determined opponent, I noticed, of the lying rich who think they can get away with anything, also like Columbo.

What, I wondered, could a tough professional like Bertrand learn from a fictional detective? I’ve asked that question more than once in the ensuing three decades, and when I do, I go back to watch reruns of Columbo.

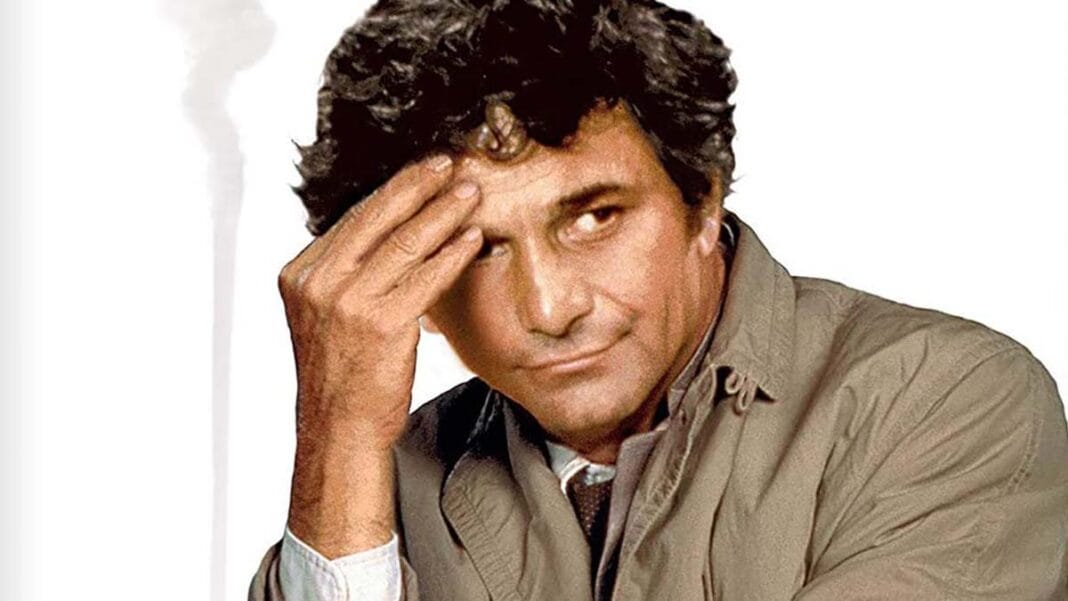

Peter Falk’s character is best remembered now for his trick of saying “Thanks for talking to me,” turning his back, and then turning again as he approaches the door to say, “One more thing.” It’s a clever trick, but you don’t need to be an investigator, or even to watch Columbo to learn it. Salesmen do it too, which is how I learned it in my first job after university. You let the other side think you’re done, and then you come back when their guard is down.

I used that gambit after Bertrand got me watching the show again, when I complimented a man who had just survived a rough session on the witness stand in a felony court, watched him relax, then asked why he had withheld a fact in his testimony. His arms shot up as he shouted, “You mustn’t say that!” It was confirmation that the fact was crucial. But if he'd noticed I was manipulating him – which is what Columbo does in these scenes – it would have been the last time we ever spoke.

I never saw salesmen adopt the single most important technique you can learn from Columbo: Let the other side under-estimate you. Let them think you’re as plodding, decrepit, vulgar and undistinguished as you look. Jean-Louis Bertrand never went that far. But on one occasion he went to encounter a violent suspect in proper street clothes, leaving his uniform at home. As for Columbo, that was a way of signalling that he was not a threat.

Columbo encourages the arrogance of his suspects to mislead them into making mistakes. Eventually, his targets will realize who they’re up against; eventually, he’ll reveal his true capability. But in the meanwhile, he has time to collect the facts that condemn them.

His first encounters revolve around flattering his suspects. (I’ve done that too, with one constraint: If a compliment is based on real facts, it’s not flattery, it’s courteous recognition.) Columbo’s compliments are thick, long and shameless. He’ll ask an aging movie star to call his wife to prove they’ve met. He’ll admire a suspect’s house, ask how much it costs, and marvel at the sum. He’ll then tell how many years of his miserable salary it would take to buy it. His flattery is welded to self-deprecation. I’m such a failure, he seems to say. If only I could be like you!

He's faking a syndrome that genuinely afflicts a great many journalists. I’ve seen students who became reporters in order to frequent people they considered better than themselves – more glamorous, famous, powerful, whatever. At crucial moments, they throw aside what they know is true, and submit to their superiors – say, by giving the "notables" the last word in a story that could have been great, as if the journalists had found nothing worth revealing. Columbo woudn't do that.

When Columbo first approaches his rich, celebrated and powerful targets, his first goal is to grasp key aspects of their characters. Do they see others as human beings, or as objects to be used and discarded? Columbo offers himself as a proxy for their victims. He moves in cringing in his cheap suit and measures the response. The way a suspect treats him – with superficial courtesy, barely-concealed disdain or threats – is the same way the suspect will treat others, if necessary by killing them.

His targets will never understand what motivates such a man, and he knows it. He embodies a class vengeance, and a democratic vengeance, against those who break the rules to stay on top.

The late Andrew Jennings, the reporter who brought down the corrupt hierarchy of FIFA – the international football organization, which since says it’s cleaned up its act – was like Columbo in that way. Jennings wrote in The Global Investigative Journalism Casebook, where his afterword is an extraordinary self-analysis of a great career: Who would you rather discomfort? The guy in the Gulfstream or the one on a bike? Like Columbo, he got in his suspects' faces, "doorstepping" them relentlessly while drowning them in questions. He very consciously adopted Columbo's persona, according to a recent memoir by one of his BBC producers, James Oliver:

At a meeting in his BBC White City office, Panorama’s then editor Mike Robinson suggested a questioning approach.

“Like the US TV detective Columbo”, Mike said. A character who in every episode of the show ended quizzical interrogations of bad guys with a scratch of the head and another question.

“Oh there’s just one more thing sir”, he’d say.

Andrew loved the idea.

I decided to take it further. In my cupboard at home I had a carbon copy of Columbo’s trademark beige raincoat. When we landed at Zurich airport to start filming Andrew was wearing it. Now he even looked like the crumpled TV detective. Andrew ran away with the idea. And my raincoat.

Most often, Jennings appeared in public wearing farmer's overalls that made Columbo's crumpled suit look like a tuxedo. Columbo is indifferent to elegance; Jennings disdained it, because in his world it was a mask pasted over corruption.

Like Columbo, Jennings could approach people with a soft voice and ask questions that operated on more than one level. The first time he attended a FIFA press conference, he brought his reputation as the scourge of the International Olympic Committee into the room. Jennings sized up the crowd, taking note of the men in blazers lined up against the wall, listening to a boss whom (he well imagined) they despised. At the end of the show he stood up and said, in a naïve tone: “Herr Blatter, do you take bribes?” He didn’t expect an honest answer. He was sending a message to the liveried servants: I’m here, I’m like you, and I’m not afraid. He wrote a story on the theme, Blatter denies taking bribes. Six months later one of those people gave him documents that underpinned his first scoop in the case.

I could never be as bold as Andrew, whom I had the pleasure of knowing. Maybe you couldn’t either. But you can live with the contempt of people who have a lot to answer for. You can believe in what you’re doing, like Bertrand and Jennings and Columbo, and draw courage from it, regardless of who despises you.

That attitude wouldn't work for Columbo, and it won't work for you if it isn't wedded to a relentless fixation on details. That obsession can mislead investigators of all kinds, because life throws up masses of facts that are irrelevant to the larger story. But some details do count, and those are the ones Columbo pursues.

In one of his greatest cases (“Etude in Black”, 1972), he meticulously pieces together details concerning the suspect’s car, which is left in a garage on the night of the murder to set up an alibi (which I paraphrase: “how could I go to my mistress’s house and kill her without a car?”). Columbo visits the garage where the car was supposedly parked overnight. He verifies the mileage that was recorded when the suspect brought it in and compares it to the mileage the morning after the murder. The mileage went up by the distance to the victim’s house, times two – a round trip. Did someone in the garage take the car for a test drive? He asks them all, and they say no. He walks the distance to the concert hall where the killer was performing that night, and notes the time required for the walk: about four minutes. It all fits together. He hasn’t closed the case, but he’s found the most likely suspect.

Jean-Louis Bertrand showed the same grinding determination. He told me, “If you want to get lucky, move your ass.” On one occasion he found a witness to a crucial moment in the lives of a criminal and her victim by going to a hotel where they had rented a room for some months. The perpetrator’s secretary had shared that room on occasion, he discovered. He got her first name, Joelle – she’d never signed the register – from the hotel clerk. What did she look like? he asked. She was pregnant, said the clerk, very pregnant indeed.

Bertrand might find her, he thought, if she’d given birth in the same county, and if she still lived there. I recounted his next steps in To Make a Killing: A true story of power, art and crime in France:

In the Vital Statistics department, he found that among the new mothers of Toulon in the fall of 1985 was one Joelle Martinez. There was an address for her in an outlying suburb. He drove there.

Someone else occupied the house and had no inkling where she’d moved.

There are 18 towns in the county, and Martinez is a very common name there. It could take a week to check them all.

He knocked on the neighbors’ doors. Finally one of them said she thought that Madame Martinez lived in a nearby town now.

He found her at her home, a newly-finished one-family house, at the end of the day on August 4. She was in her twenties, short, slender and cleft-chinned with heavy, long brown hair. She listened, with a surprised expression, while he introduced himself and explained his business.

Is she the one? he wondered.

Then she surprised him.

“I’ve been waiting for someone to come see me,” she said. “There was just something wrong, I always knew it.”

Bertrand said, testing her, or testing his own luck: “Maybe you want to reflect a little, before we talk.”

“No,” she said. “I don’t need to reflect. I’m ready.”

You cannot be Columbo, of course. You can be like Columbo, and still be yourself – courteous like Bertrand, joyously ferocious like Jennings. You can remember why you're doing the job – "chasing bad men," said Jennings – and for whom: the ordinary, honest people. The guy on the bicycle. In other words, the people who were betrayed by their betters. You can't arrest their victimizers if you're a journalist, but you can expose them. If you're like Columbo, you'll find it hard to think of anything better to do.