Mediapart aimed at investigative reporters. USAID took the hit.

- The leading French news outlet Mediapart’s “revelations” concerning the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project's "hidden" links to the U.S. government were published after eight years of stories that made similar allegations in Russian state-linked media about the OCCRP.

- Mediapart’s story proceeded from a groundless premise of concealment, omitted key evidence and included erroneous “facts”.

- Mediapart’s story was used to justify reprisals against journalists worldwide and supercharged the Trump administration’s annihilation of USAID.

By Mark Lee Hunter

On April 4, 2016 — the day after the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists began publishing the Panama Papers, an investigation of rogue offshore finance that implicated Vladimir Putin’s inner circle in money laundering and later won a Pulitzer Prize — a series of mysterious posts began appearing in an online forum in Russia.

The posts accused the nonprofit Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, a key partner in the Panama Papers and a relentless journalistic adversary of Russia’s corrupt oligarchs, of being “tightly attached to the financial needle of the State Department and USAID [U.S. Agency for International Development]”, and of being “for the same reason… an instrument of American foreign policy.” The pseudonymous author abundantly cited open sources from the U.S. government’s “transparency” websites, like usaspending.gov, to prove their case. Similar stories immediately appeared in the state-controlled media Pravda and RT.

Outlets in Russia and Azerbaijan — where the ruling Aliyev family was a regular target of OCCRP’s investigations, and where OCCRP reporters were imprisoned in 2015-16 and 2017-20 — and even France recirculated that narrative at least 65 times in the coming years.

It was no surprise to the OCCRP, an iconic organization in investigative journalism, founded in 2008 to expose criminality and build journalistic capacity in Eastern Europe. "We knew everything that was said about us in Russian,” commented OCCRP co-founder Drew Sullivan. “They’ve been trying to get that into the Western press forever. They were promoting it on social media. You do that because you want it to go viral, and nobody would spread it. "

On December 2, 2024, the respected independent left-wing French news outlet Mediapart published an investigation of OCCRP in collaboration with Drop Site News in the U.S, Reporters United in Greece and Il Fatto Quotidiano in Italy.

Mediapart headlined: “The OCCRP, the largest organised network of investigative media in the world, hid the extent of its links with the US government, this investigation can reveal.” The text explained that OCCRP “conceals the extent of [its government] funding and the strings attached to it from its media partners, journalists and the wider public.” Thus hidden U.S. funding enabled and cemented U.S. control of OCCRP’s content, its investigative targets and even its leadership, claimed Mediapart; and that control served to “weaponize” investigative journalism against Russia, the first among countries “governed by autocrats who Washington regards as enemies.”

The dangers of this narrative for OCCRP were higher than Mediapart acknowledged. OCCRP is a key driver of investigative journalism worldwide, and a priority target for corrupt oligarchs and politicians. A journalist who partnered with OCCRP, Ján Kuciak, had been assassinated with his fiancée in Slovakia in 2018. That fact is absent from Mediapart’s account, which said only that OCCRP reporters risk imprisonment or exile. Mediapart also left out kidnapping, which is how Azerbaijan got its hands on another OCCRP partner at Tbilisi, Georgia in 2017. In April 2022, the editor in chief of OCCRP partner Novaya Gazeta, Nobel Peace Prize winner Dimitry Muratov, was brutally assaulted in the Moscow subway. Since Vladimir Putin took power in Russia, 37 reporters were killed there, according to Reporters Sans Frontières. Those are the risks that OCCRP accepted.

Mediapart were given ample opportunity to reply to my repeated requests for comment on points that concern them in this article, in particular while an earlier and largely identical version was in production at the Columbia Journalism Review (CJR). In a letter to executives of CJR and the Columbia Journalism School last March, co-author Stefan Candea wrote, “it would be totally unacceptable for Mediapart to be falsely and slanderously portrayed… directly or indirectly, as serving the interests of Russia and/or its propaganda.” Mediapart were provided with a full, fact-checked copy of that version – an extraordinary procedure and privilege – with my accord, in consideration of their record as a leading voice in French journalism, for which I have repeatedly expressed my admiration since 2017, as well as in my commentary on their article published on their website the night it came out. I also provided them with a list of Russian articles that had attacked OCCRP, including their URLs, and a verified spreadsheet of all U.S.-focused investigations by OCCRP.

They demanded that I be excluded from further discussion of the project, to which CJR acceded. Mediapart sent CJR an extensive rebuttal, on condition that I not be allowed to see it. CJR dropped the project. (Coincidentally or not, Columbia University was simultaneously embroiled in a confrontation with the Trump administration, who appear in the story.) As this updated story was nearing publication, Mediapart refused to reply to the same questions I had asked previously, on the grounds that they were now “caduc” – null and void – because of CJR’s decision, and refused again to share their rebuttal to CJR. They have repeatedly said that they stand by their story, and I stand by mine. As they said of their article, the project you are reading has been “painful but necessary”, in order to complete and correct the record.

Mediapart’s story lit a fire of reprisal that burned in Moscow, Valletta (Malta), Baku (Azerbaijan), New Delhi (India), Belgrade (Serbia), Bratislava (Slovakia), Djakarta (Indonesia), Budapest (Hungary) and Washington, where the journal’s accusations supercharged the smashing of USAID, the American agency that funded democracy and life-saving foreign aid the world over.

It would be terribly unfortunate if the story were true, and worse if it were not.

A groundless hypothesis

Mediapart’s sensational premise that OCCRP “conceals the extent of [its U.S. government] funding” is groundless. It was never concealed that OCCRP had received major funding – an average of about half the total of its support over the years, as Mediapart says – from the U.S. government since their founding in 2008. Even Russian media noted that OCCRP "do not hide the fact that their activities are funded by USAID (United States Agency for International Development)."

Their campaign against OCCRP was predicated on public, open source documents. Mediapart’s story relies on those same documents. Like virtually any other American non-profit organisation, OCCRP are required to file detailed public disclosures and independent audits every year, where their revenue sources, expenses, and even the salaries of their executives are reported. (You can’t get that level of detail from Mediapart’s own disclosures.) Whatever else it may be, this material is neither hidden nor a fresh revelation. Mediapart’s co-author Stefan Candea evokes it in his 2020 doctoral thesis, which notes that “the majority” of OCCRP’s financing came from USAID.

Mediapart recount “that the OCCRP did not, as a matter of course, inform its own members or media partners of the extent of its funding by the US government[.]” At least concerning “its own members”, the accusation is untrue, according to Sanita Jemberga, who runs the Baltic Center for Investigative Journalism, based in Riga, Latvia, and represents OCCRP’s 71 media centers on its board. OCCRP discloses its finances to them thoroughly, she said, “since we have to approve annual reports and are informed about fundraising strategy.” Anything but the complete transparency she sees from OCCRP, she added, would undermine trust “in an environment which is sensitive.” Riga harbors numerous Russian exile media and intelligence operatives; it is not a place to take naïve risks.

Mediapart acknowledge that evidence they gathered through calls to OCCRP’s partners goes against their charge: “Most of those members of the OCCRP who did reply to us [some didn’t] simply said that they knew the organisation received funding from the US government, a fact that is well-known [emphasis added].” They then speculate that an email later sent to OCCRP’s partners by Sullivan to provide details of its financing “demonstrated that he had not previously informed them.” Other explanations are possible. For example, it could also demonstrate that they didn't think it necessary to inform themselves beyond what they already knew. Mediapart then quote their competitor and OCCRP partner Le Monde: “Nothing…in the OCCRP’s explanations about its manner of functioning prompts us to place in question our relationship of confidence.”

On the one hand, Mediapart are scrupulous in quoting sources who challenge their premise. On the other hand, the challenges do not apparently alter their argument.

Mediapart’s work is punctuated by mistakes that have the effect of making OCCRP look bad.

- Mediapart omit a key fact. They ignore that from 2012-22, USAID paid nothing directly to OCCRP. The money went to the respected non-profit International Center for Journalists (ICFJ). They took a share for managing OCCRP’s administration, and they said they were “an extra layer of insulation” between OCCRP and the government. In other words, there was a structural obstacle to direct government control. ICFJ said that Mediapart's team never contacted them.

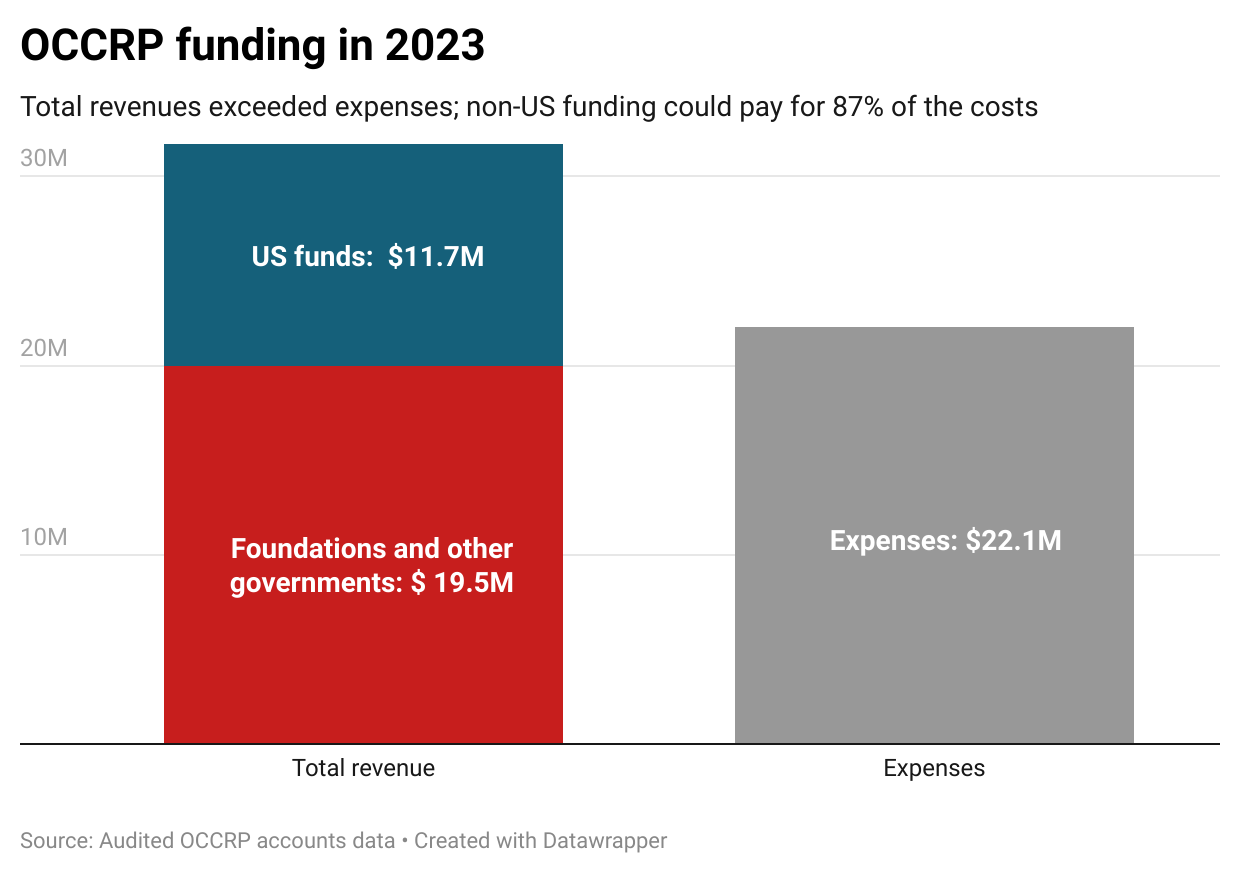

- Mediapart cherrypick a key number to suit their argument: They say that in 2023, OCCRP received $11.7 million in U.S. government grants, “which represented 53% of its expenditure that year.” That same year, the most recent for which we have data, OCCRP also received $19.5 million from private sources and other governments, which represented 87% of the same expenses. In other words, the U.S. accounted for a clear minority of OCCRP funding in 2023 (and several other recent years). Mediapart don’t mention that.

- Mediapart use an erroneous “fact” to support their charge of concealment. They told their readers that “the OCCRP appears uncomfortable about the scale of US funding, as the amounts are not published on the NGO’s website.” That information is contained in OCCRP’s annual reports, which are accessible on its website.

Unsupported accusations of U.S. control

One of Mediapart’s major claims is that “not only is the US government largely untargeted by OCCRP reporting, but it also manages to orientate the NGO’s coverage by providing funds”. Indeed, said Mediapart, OCCRP is “barred” from covering U.S. subjects with American money, if not entirely.

The argument resembles the Russian narrative on OCCRP since 2016: “Have you already noticed that there are no Americans in the [Panama Papers] investigation? [In fact, 36 Americans were named in the story.] Is it because the sponsors of ‘investigative organizations’ are sitting in Washington? It's an old story – he who pays, approves.”

Mediapart left out that USAID's contracts with OCCRP give the newsroom total control over its work, though their team was so informed. In the summer of 2023, USAID sent an email message to the German broadcaster Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR), which initiated the investigation and then dropped it before Mediapart published. The email quotes from OCCRP’s contract with USAID: OCCRP “retains sole control over the editorial processes during the performance of this agreement …. [OCCRP] will solely decide which stories it reports and publishes[.]”

In other words, not only did USAID have no contractual right to direct OCCRP’s content, it had a contractual obligation not to do so.

The ICFJ, who managed OCCRP’s grants from USAID for a decade, said that “USAID never directed us on content, and we never directed OCCRP.”

Mediapart provide a single example to back their claim. At the end of the 2000s, OCCRP considered a story about highway construction in several Balkan countries, especially Albania, where the U.S. engineering firm Bechtel was implicated in corruption scandals. Quoting OCCRP’s internal emails, Mediapart show that the OCCRP considered but “did not cover the story of the alleged corruption.” Their only evidence is nearly 20 years old and does not explain why OCCRP might have dropped the case, unless self-censorship is assumed.

There’s better evidence for other explanations. OCCRP said they left Bechtel aside because at the time they were a skeleton crew focused on investigating tobacco trafficking. Moreover, the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, which both competes and collaborates with OCCRP and likewise gets funding from European and American aid agencies, produced nine investigative stories on Bechtel’s affairs in the Balkans from 2011-24. In journalistic parlance, they owned the story. Sullivan said there was no point in competing with them. BIRN said they saw no evidence that the U.S. controlled OCCRP’s work.

Mediapart report that Sullivan said in 2023 that “in the early years […] We couldn't use US government or Soros money [the Open Society Foundation was also a funder then] for US stories.” Even today, that would be “a conflict of interest”, Sullivan told Mediapart. That’s a statement of ethics, not an admission of self-censorship.

Mediapart quote a Latin American partner of the OCCRP: “We have collaborated with them in stories that were particularly critical about US drug policies[,] or about US migration policies [and] they never expressed having a problem with this.” Mediapart then refer to three more OCCRP stories about American subjects, and say: “Nevertheless, those investigations represent a small part of the OCCRP’s total production.”

That leaves out 111 other investigations of American entities and individuals from 2015-24, including members or associates of the Trump and Biden administrations, whom Mediapart said were “largely untargeted”.

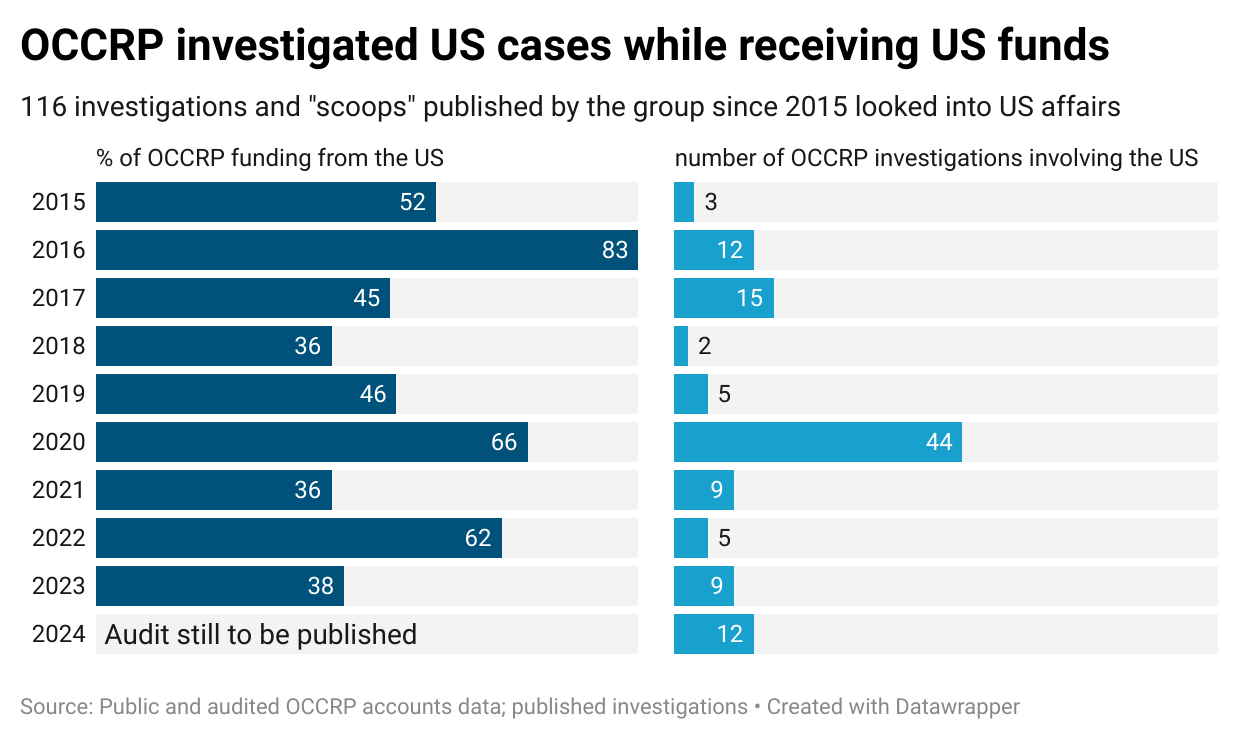

I asked OCCRP to provide a spreadsheet of U.S.-focused investigative stories in that decade (I verified every one), because their security protocols blocked me from scraping their website. I informed them that I would test the following hypothesis: As U.S. funding rises, stories about the U.S. will decline. In other words, I tried to prove Mediapart’s theory that U.S. funding controlled OCCRP’s editorial choices, which is one way to counter potential bias. I also told OCCRP I would publish the results, whatever they turned out to be.

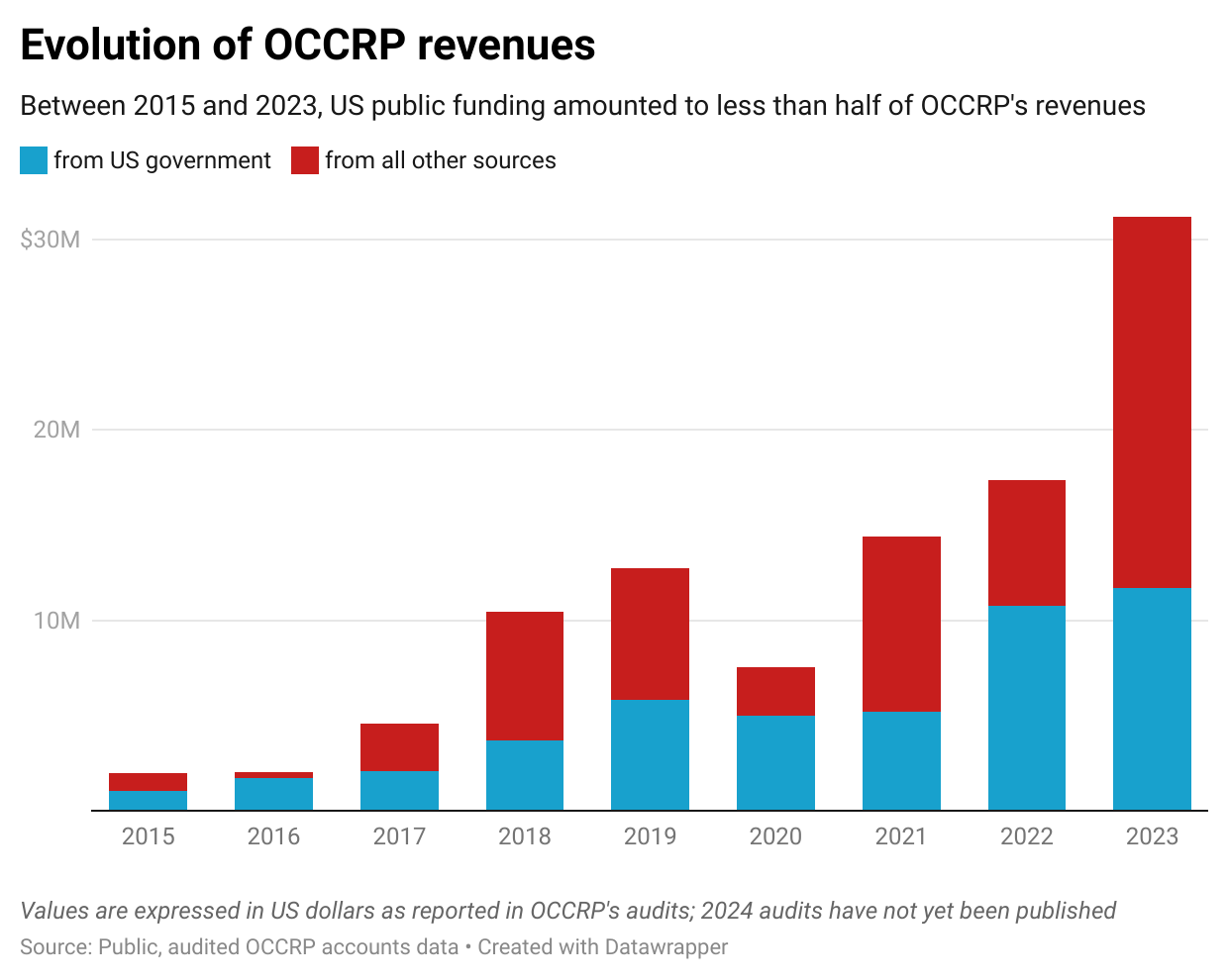

The data show that as OCCRP’s U.S. funding increased over the years, so did investigations of U.S. affairs (see our chart below). That’s the opposite of what you’d expect if the American state were calling the shots.

Mediapart note: “Sullivan and the [OCCRP] board told this investigation that the restriction of not using US funds to investigate US issues is not a problem given that the NGO can use other, non-US funds it receives to do so.” But Mediapart did not visibly verify the statement, which is supported by the data: As U.S. funding rose, non-American revenues grew even faster, to over half the total, and so did investigations of Americans.

And, even in years when American funding accounted for a majority of OCCRP’s revenues, it published investigations of American subjects.

Mediapart also claimed that Washington could “veto” OCCRP’s leadership, which at least one outlet interpreted to mean that the American state could choose who ran OCCRP, including its editors. But Mediapart don’t show a single example of USAID naming or vetoing anyone at OCCRP. The reason, Sullivan said in writing, is that “there were no examples” to cite.

According to Sullivan, two of OCCRP’s 19 grant agreements with USAID since 2007 gave the agency a right of “approval” and “notification” over specified “key” roles. Editorial roles are not mentioned in the most recent agreement – the relevant passage was published by OCCRP – and Sullivan said the same applies to the other one. The latest agreement mentions the “chief of party,” or Sullivan. USAID had no right to replace him, said Sullivan. The other specified role is a “safety and security” specialist. USAID did, in fact, dispute OCCRP’s choice for that job, and Sullivan said that he hired the person he wanted anyway. (I confirmed it independently.) He explained: “They can’t make you put in someone” – indeed, there’s no such provision in the published contract with USAID – “and if we said ‘no’ there wasn’t anything they could do about it except maybe try to terminate the grant.”

Sullivan was quoted to that effect in Mediapart’s story: If USAID tried to impose anyone on OCCRP, he said, “then we can say we don't take the money.” Mediapart counters: “But that tempts the question as to whether the OCCRP could really say no to such a large contribution to its budget.” Events since their story was published show that OCCRP could: After Donald Trump shut down USAID, OCCRP laid off 43 of its 200-odd employees, and remained in business.

Mediapart further claimed that the U.S. “weaponized” OCCRP’s reporting against Russia and its oligarchs, notably by using OCCRP’s work to support prosecutions of sanctions violators. But Mediapart regularly take note of the prosecutions that their exposés unleash in France, and that is perfectly normal. The precise role of investigative reporters is to alert authorities and the public to threats against the public good. That’s why scholar James T. Hamilton calls them “Democracy’s Detectives.” Exposing sanctions violators falls within the job description.

Mediapart's arguments contributed to immediate, grave and ongoing consequences for journalists worldwide.

Hunting season for autocrats

In an editorial that accompanied their exposé, Mediapart ironized: “We can already hear the malicious gossip… according to which we are the ‘useful idiots’ of Putin’s Russia[.]” Instead, said Mediapart, the OCCRP had “played into the hands of the planet’s worst dictators” by “hiding” its U.S. government ties. According to Mediapart, their story was “necessary” because OCCRP had damaged “the relationship of confidence that should unite those who produce the news (journalists) with those who receive it (citizens).”

The Russians immediately responded to the news. “Soros, sanctions, propaganda: How the US government secretly controls the ‘world’s largest investigative journalism organization’”, headlined RT, the Russian state-controlled network, in an article that reported on Mediapart’s claims. On Dec. 5, Russian prosecutors raided the home of the parents of Alesya Marokhovskaya, the award-winning editor-in-chief of OCCRP partner IStories, accusing her of failing to disclose ties to “foreign agents.” In January, they issued a warrant for her arrest.

It was no surprise to anyone who follows such events. Major state-linked Russian media, notably RT, had monitored OCCRP’s Russian partners in-country and in exile for years. In 2021 RT had called them “an international conglomerate that is very actively fighting Russia and its allies.”

In Malta, where investigative reporter Daphne Caruana Galizia was murdered in a 2017 car bombing, the ONE News network, aligned with the country’s corruption-plagued Labour Party, cited Mediapart while targetting Times of Malta journalist Jacob Borg, who works with OCCRP. Expert observers warned that this could be a prelude to another assassination. Mediapart declared that it “strongly condemns the manipulation of its recently-published investigative article” to “attack individual journalists.”

The attacks kept coming. In India, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party alleged that a conspiracy by “a global news portal [OCCRP]”, George Soros and the American “Deep State” – all mapped in Mediapart’s exposé – was seeking to disrupt the Indian government and called Rahul Gandhi, leader of the opposition Indian National Congress, a traitor “of the highest order.” Mediapart protested again. OCCRP journalist Anand Mangnale, already under investigation by Indian authorities, was targeted. He said: “They’ll make it a big issue, then file new cases. That’s a playbook they’ve been using for a while now.”

The same playbook appeared in Azerbaijan,where on Dec. 3 an English-language website owned by the Global Media Group, which operates seven print, broadcast and online media in the country, falsely claimed that Mediapart’s story showed that the U.S. government “appointed” OCCRP’s leadership – that’s how disinformation works – while other outlets took up the story in Azerbaijani. Three days later, the authorities descended on OCCRP partner Meydan TV. Their site says: “The Azerbaijani authorities have imprisoned seven of our journalists in an attempt to silence them, and us. We won't let this happen. As Azerbaijan's leading source for unbiased, quality independent news and information, we will continue the work our seven jailed journalists believed in and serve our audiences.”

More payback came in Serbia, and still more in Indonesia, where OCCRP was accused of threatening the “national sovereignty.”

Further reprisals, and the most far-reaching, came in the U.S. The day after Mediapart’s “investigation” was co-published with U.S.-based Drop Site News, the Daily Caller, a MAGA-allied outlet, quoted them in denouncing a 2019 OCCRP article that exposed Rudy Giuliani’s activities on behalf of Donald Trump in Ukraine. OCCRP’s article had been cited four times in the whistleblower complaint that led to Donald Trump’s first impeachment. Mediapart hadn’t mentioned that fact. But Drop Site News did and thereby put it on the American agenda.

Mediapart and its consortium had promoted the idea that OCCRP was launched by the Deep State – specifically, “a U.S. army officer” who later did intelligence work – under cover of USAID, to attack Russia. Trump had long since promised retribution for his first impeachment and the “Russia Hoax” behind it. His MAGA media allies would now connect those dots, with OCCRP at their center. They would be helped by the likes of “The Daily Fetched”, an avowed “constant ally” of American conservatives, registered in London and present on various far-right social channels. Their “about us” page uses curious diction like “old American values” and “the mainstream media [are] trying to quiet our voices”. Their story about the OCCRP, based on Drop Site's article, noted: “a large bulk of OCCRP’s U.S. government-backed work focused on countering Russian media narratives.”

That same day in Washington, Heritage Foundation Vice President for Communications Mary Vought—whose company published Project 2025, the Trump administration’s unofficial program blueprint — retweeted the news about OCCRP, saying it “looks like a great place” for Elon Musk to start cutting Federal programs.

Stefan Candea, the co-author of Mediapart’s exposé, warned in a LinkedIn post just before Christmas that there was still big money “for weaponising journalism at USAID and in the large coffers of the US Government.” He went into detail about “the weaponising it will bankroll: independent media, investigative journalism, and civil society watchdog groups working to combat corruption [and] encourage cooperation with social media entities to strengthen the integrity of information on the Internet". Soon this entire global infrastructure that had opposed autocratic interests and promoted rule of law would be swept away.

Candea’s attack on U.S. support for journalism and civil society wasn’t guaranteed to have effects. Before Donald Trump took his oath as President, there were no plans to dismantle USAID. Project 2025 called only for eliminating assistance to programs that promoted liberal priorities like abortion, climate and gender and building ties to religious institutions, while maintaining USAID’s life-saving medical and food assistance around the world. The document has harsh words for the Voice of America, National Public Radio and the Agency for Global Media, but says nothing about USAID’s grants to media around the world, and OCCRP isn’t mentioned either.

Trump moved swiftly to remake USAID. On his first day in office, he imposed a 90-day pause on USAID programs, and within a week, the agency’s top brass were put on leave.

At the beginning of February, after USAID personnel refused to allow a DOGE team unfettered access to their files and systems, Elon Musk denounced USAID as a “criminal organization”. (Mediapart had jokingly asked if OCCRP were a “criminal organization” in a newsletter on December 7 promoting “this investigation”. Musk was not joking.) He said that USAID must “die”, and that he had Trump’s full support for destroying it.

An independent journalist named Michael Shellenberger built on the work of Mediapart and Drop Site News to portray OCCRP and USAID as co-conspirators in a plot with the CIA to impeach Trump in 2019. His “smoking gun” was OCCRP’s 2019 article on Giuliani’s Ukraine operations. Shellenberger’s articles got him on Fox News, and earned him wide coverage on MAGA websites, including Infowars, National File, The New American, The Daily Signal, Geller Report (“TREASON: USAID Funded Fabricated Evidence Used to Impeach President Trump”) and others. On Feb. 12, he testified to the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs that “CIA, USAID and OCCRP were all involved in the impeachment of President Trump in ways similar to the regime change operations that all three organizations engage in abroad.” He called that “highly illegal and even treasonous”. His testimony recites long passages of material from Drop Site News, Mediapart and Candea's doctoral thesis.

In the European Union, illiberal politicians and their media allies likewise seized on this new opportunity to hammer journalists who hold them accountable.

Mediapart’s exposé was immediately reprised in Hungary last December by outlets close to Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, whose policies are considered a model by Trump’s MAGA movement. One said: “the French Mediapart and its partners published a report that sheds light on the ownership background of OCCRP, its sources of funding, its true goals and objectives, and everything that has been going on under the guise of this venerable international organization.” In early February, Direkt36, an OCCRP partner, released “The Dynasty,” a documentary that exposed the “economic empire” of Orban’s family. The film was seen 3.7 million times on YouTube, in a country with a total population under 10 million. On February 6 Orbán declared that the time had come to “eliminate… people and organisations paid from abroad whose job is to overthrow the Hungarian government".

On the night of May 14th, Orbán’s Fidesz party submitted a bill to the Hungarian Parliament “On the Transparency of Public Life” that targets NGOs, independent media and opposition parties who accept foreign donations. It’s a variation on the Russian “foreign agent” laws that were used by Putin’s government to threaten OCCRP’s partners, and which have lately been adopted in Georgia. The move set off a crisis across the European Union, as major press outlets and human rights organizations and the European Commission denounced the bill.

In Slovakia, the 2018 murder of OCCRP’s partner reporter Ján Kuciak had led to mass protests against the government of Prime Minister Robert Fico, who was forced to resign – a unique event in the history of investigative reporting. But Fico is now back in power. On February 10 he wrote to Elon Musk to say that it was “undeniable” that USAID had tried to “distort the political system” in Slovakia, and requested “information available on subsidies and grants provided to non-governmental organisations, media outlets and individual journalists” working in Slovakia.

The end of USAID

On March 28, USAID was shuttered for good. Over 9000 people who had spent their careers building democratic institutions worldwide lost their jobs and vital benefits like health insurance.

Smashing USAID led to a “nightmare” for investigative media worldwide, particularly in Ukraine, reported the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN). It was also a disaster for climate journalists, gender journalists, and democracy advocates (to say nothing of those who relied on USAID for lifesaving food and medicines). A seminar for World Press Freedom Day in Brussels on May 6 captured the mood in its title: “The Global Funding Crisis of Independent Media”. At the seminar, a Colombian journalist told how the cancellation of USAID had increased the danger for journalists investigating human and drug trafficking, because they could no longer pay for security measures.

For journalism, there will be a before and after March 28. According to Paris-based Reporters Without Borders, in 2023 alone, USAID had funded training and support for 6,200 journalists, assisted 707 non-state news outlets, and supported 279 media-sector civil society organizations. Since then the MAGA movement laid waste to the voices of the free world, while making use of polemical resources created by Mediapart and its consortium.

There were consequences for Mediapart, too. Its project at least temporarily complicated relations with its collaborator, German broadcaster Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR), which initiated the exposé as a film about OCCRP, then dropped the project. According to Mediapart, NDR had “censored” the story after Sullivan “pressured” them to check their facts and “weigh the damage” it might cause. NDR’s senior managers replied to Mediapart, “We strongly reject your judgment, conclusion and narrative.” According to the Frankfurter Allgemeine-Zeitung, NDR dropped the story after their autonomous units declined to publish the story and their legal team raised questions. MAGA media took Mediapart’s claim as "proof" that they had revealed dark secrets.

Mediapart’s reputation as an exemplar of investigative excellence has been weakened. The Global Investigative Journalism Network, the world’s leading organisation in the field, which had previously promoted “the keys to the success” of Mediapart on its website, declared in a board statement (from which members who collaborate with OCCRP recused themselves) that “GIJN sees no evidence of influence or pressure from its funders on OCCRP’s work nor evidence that its editorial content has been guided or changed in any way.”

Thanks to the autocrat media sphere, the story in one form or another will remain on the Internet, where “it will definitely blow again and again and put us all in danger,” said Pavla Holcova of OCCRP partner media investigace.cz, who worked with Ján Kuciak at the time he was murdered.

A new era for investigative journalism

Investigative journalism has entered a new era, and not only because much of its funding has been amputated. For the Trump administration, Russia isn’t an adversary anymore, and corruption isn’t a target either. Whatever comes next, OCCRP and other investigative journalists will have to invent a new path forward, because the American state no longer shares their values.

That’s not Mediapart’s fault, but it’s certainly in line with the logic that underpins “this investigation”. If it was wrong for OCCRP – who risked their lives to stand up to criminal forces, and in the process won scores of national and international awards for their work – to solicit and accept taxpayer money, a point that Mediapart repeatedly insists on, then it’s forcibly wrong for everyone else. That argument would preclude what remains of democratic support for media anywhere, at a moment when other revenue streams, like advertising or subscription, are at worst insufficient and at best under development, and while state-funded disinformation is multiplying. That won’t directly hurt Mediapart, who are supported by their readers and donations, but it’s bad news for many others on whom the investigative journalism ecosystem depends. At this writing Drop Site News, whose founder, Ryan Grim, has contributed to three admiring books about U.S. congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, continues to hound OCCRP for its funding practices.

There has been enough damage. It took 20 years for investigative journalists, foundations and democratic governments to build a global movement of free media, facing deadly enemies. It took a few months for left-wing journalists and right-wing politicians, working independently, to kneecap the movement. For everyone else, it’s a damn shame. Democracy would not be better off if OCCRP and USAID had never existed, and it is not better off because of “this investigation.”

About the author

Mark Lee Hunter is a founding member of the Global Investigative Journalism Network and the principal author of Story-Based Inquiry: A Manual for Investigative Journalists (2009) and a dozen other books. Disclosure: In the past 26 years he has worked as a journalism trainer and consultant in programs and with organisations funded directly or indirectly by the U.S Dept. of State as well as the Dutch, Danish, German, Swedish and U.K. governments and private foundations. He has never been employed or remunerated by OCCRP. See his complete bio.